Many things that we take for granted in our daily life were passed down from the medieval Muslim world. From the way we eat, to the soap we use to wash our faces, a host of inventions have shaped our life style. We can’t underestimate the importance of Muslim influence on Europe and Spain in particular.

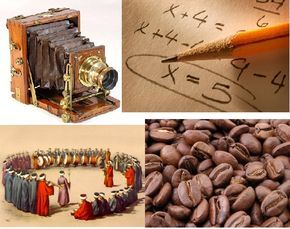

Coffee, for example—a cup of which is essential for me to start the day, and which I always thought originated in the Americas—is supposed to have been first discovered by an Arab goatherd in Ethiopia, who noticed that his animals became very lively after eating a particular wild berry. He decided to try it for himself and boiled some up to make the first coffee. Millions of people have enjoyed it ever since.

As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention and it is very true. Cleanliness is stipulated in Islamic religious teachings as essential before prayer, so there was a constant demand in the Muslim world for decent quality soap. They needed to improve on the crude soap used by the Romans, so they mixed vegetable oils with sodium hydroxide, adding some sweet smelling herbs and produced a soap almost identical to that which is used today. One of the things the Muslims always found hard to understand was the Christian attitude to cleanliness and their strong body odour.

A putrid smell permeated Christian homes as well, because their floors were made of earth and covered by rushes, or rush mats which were changed infrequently. Consequently, over the years the filth accumulated under the rushes and began to smell. In Muslim Spain and other parts of the Muslim world, carpets and rugs woven from wool, and sometimes silk, were used to cover the floor. Their intricate designs and bright colours made the carpets decorative as well as functional and the idea of spreading carpets on the floor soon spread throughout Europe.

Coffee, for example—a cup of which is essential for me to start the day, and which I always thought originated in the Americas—is supposed to have been first discovered by an Arab goatherd in Ethiopia, who noticed that his animals became very lively after eating a particular wild berry. He decided to try it for himself and boiled some up to make the first coffee. Millions of people have enjoyed it ever since.

As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention and it is very true. Cleanliness is stipulated in Islamic religious teachings as essential before prayer, so there was a constant demand in the Muslim world for decent quality soap. They needed to improve on the crude soap used by the Romans, so they mixed vegetable oils with sodium hydroxide, adding some sweet smelling herbs and produced a soap almost identical to that which is used today. One of the things the Muslims always found hard to understand was the Christian attitude to cleanliness and their strong body odour.

A putrid smell permeated Christian homes as well, because their floors were made of earth and covered by rushes, or rush mats which were changed infrequently. Consequently, over the years the filth accumulated under the rushes and began to smell. In Muslim Spain and other parts of the Muslim world, carpets and rugs woven from wool, and sometimes silk, were used to cover the floor. Their intricate designs and bright colours made the carpets decorative as well as functional and the idea of spreading carpets on the floor soon spread throughout Europe.

In the 9th century, an Arabic scientist, Jabir ibn Hayyan invented the process of distillation, and as many of his processes and equipment are still used today, he could be said to be the founder of chemistry. Although his discovery of the method of distillation meant that alcoholic spirit could be made, the Muslim religion forbade them from drinking it. One wonders if ibn Hayyan just had the odd taste himself.

In the middle of the 10th century, the Sultan of Egypt wanted someone to invent a pen that wouldn’t stain his hands with ink, so one ingenious man came up with the fountain pen, which functioned on exactly the same lines as today’s fountain pen with a small reservoir to hold the ink.

In the middle of the 10th century, the Sultan of Egypt wanted someone to invent a pen that wouldn’t stain his hands with ink, so one ingenious man came up with the fountain pen, which functioned on exactly the same lines as today’s fountain pen with a small reservoir to hold the ink.

The garden was always a special place for the people of Muslim Spain, and their palaces and homes demonstrate this; you only have to visit the wonderful gardens in the Alhambra in Granada to realise how much care and attention they gave to them. For the Muslim in al-Andalus it wasn’t enough to just have kitchen and herb gardens to provide fruit, vegetables and aromatic herbs, they also built pleasure gardens for meditation and tranquility. Beautiful spaces with running water features, ponds filled with golden carp, marble pathways and flowers and shrubs that gave colour and fragrance to the garden. To them they were places of beauty, somewhere to sit and read or simply relax.

The list of inventions bequeathed to us by medieval Muslim scientists could go on and on: the pin-hole camera (Camera Obscura), the game of chess, the crank-shaft, the combination lock, the art of quilting, the windmill, the technique of vaccination, even the modern cheque, which was invented in the 9th century to remove the risk of transporting large sums of money over dangerous territory, and many surgical instruments which have not changed their design in a thousand years. In the Middle Ages Muslim scientists were prolific in their inventions and their writings.

Many new ideas were brought to Spain by a man called Ali ibn Nafi who arrived in al-Andalus in the 9th century from Bagdad. You may recognise him better by his nickname of Ziryab, the blackbird, so called because of his dark skin and his beautiful singing voice.

I have written about Ziryab before, concentrating on his influence on the Umayyad court on Córdoba in terms of fashion, hairstyle, eating habits and food, but he was primarily a singer, a poet, and a composer. He also played the oud. When he arrived in al-Andalsu he went straight to the emir, looking for a new life and a way to further his career. It was a good move. He soon became immensely popular with Abd al-Rahman II, and was paid a large salary to stay at the court, where his influence touched all parts of society.

Not only did he entertain the emir with his playing and singing, but he also set up a music school and trained many young musicians. It is said the Andalusian classical music dates back to the emirate of Cordoba, to the time when Zirab was working there.

I have written about Ziryab before, concentrating on his influence on the Umayyad court on Córdoba in terms of fashion, hairstyle, eating habits and food, but he was primarily a singer, a poet, and a composer. He also played the oud. When he arrived in al-Andalsu he went straight to the emir, looking for a new life and a way to further his career. It was a good move. He soon became immensely popular with Abd al-Rahman II, and was paid a large salary to stay at the court, where his influence touched all parts of society.

Not only did he entertain the emir with his playing and singing, but he also set up a music school and trained many young musicians. It is said the Andalusian classical music dates back to the emirate of Cordoba, to the time when Zirab was working there.

One Sunday morning a friend rang to tell me that there was a programme on the BBC’s Radio 3 about early music and they were looking at the music of al-Andalus. He warned me it was rather long, almost three hours.

The programme was mostly examples of medieval classical music, along with information about the subject and interspersed with interviews from various experts. Some things surprised me. It’s easy to imagine that the only time Muslim al-Andalus and Christian Spain came into contact was on the battlefield, but apparently there were many Muslim and Jewish musicians in the Christian courts of medieval Spain, where Arabic music was greatly appreciated. The spirit of cultural convivencia continued in al-Andalus during the Middle Ages with examples of Jewish poets writing in Arabic for a Christian audience. In other aspects of the arts this cross cultural intermingling was also very evident in design and architecture. As with much of the history of that time, information is sparse and music historians have to rely a lot on conjecture, oral traditions and the interpretation of more recent examples of the type of music that is played in North Africa and the Middle East today.

We do know some of the instruments that were used at the time, from carvings and sculptures, like the one on the Gate of Glory in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, showing two men playing an organistram, an early version of the hurdy-gurdy. Another image of that particular instrument is in the museum of Rouen, from the abbey of St Georges de Boscherville, with two women, a lady playing the keys and her maid turning the handle. The manufacture and design of musical instruments began in al-Andalus in the 10th century: lutes, rebecs (bowed stringed instruments which were possibly the fore-runner to the violin) guitars and nakers ( pairs of round drums) soon spread across Europe.

The programme was mostly examples of medieval classical music, along with information about the subject and interspersed with interviews from various experts. Some things surprised me. It’s easy to imagine that the only time Muslim al-Andalus and Christian Spain came into contact was on the battlefield, but apparently there were many Muslim and Jewish musicians in the Christian courts of medieval Spain, where Arabic music was greatly appreciated. The spirit of cultural convivencia continued in al-Andalus during the Middle Ages with examples of Jewish poets writing in Arabic for a Christian audience. In other aspects of the arts this cross cultural intermingling was also very evident in design and architecture. As with much of the history of that time, information is sparse and music historians have to rely a lot on conjecture, oral traditions and the interpretation of more recent examples of the type of music that is played in North Africa and the Middle East today.

We do know some of the instruments that were used at the time, from carvings and sculptures, like the one on the Gate of Glory in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, showing two men playing an organistram, an early version of the hurdy-gurdy. Another image of that particular instrument is in the museum of Rouen, from the abbey of St Georges de Boscherville, with two women, a lady playing the keys and her maid turning the handle. The manufacture and design of musical instruments began in al-Andalus in the 10th century: lutes, rebecs (bowed stringed instruments which were possibly the fore-runner to the violin) guitars and nakers ( pairs of round drums) soon spread across Europe.

We also know of the songs that were sung in al-Andalus because many poems have survived in the anthologies of famous poets, such as ibn Bassam, an eleventh century poet and historian. Poetry was a much admired skill, and there were both men and women poets, although fewer of the names of female poets have survived. One Muslim princess had her favourite poem embroidered into her dress.The people of al-Andalus made no distinction between a poet or a song writer, so we can assume that a great deal of the poems that have been saved may well have been sung, rather than recited. Many of the songs were often repetitive, sometimes no more than one line, and usually accompanied by the oud, the forerunner to the lute, or by the rhythm of a beating drum and clapping. Much of the music was lively and it is easy to imagine the swirling skirts of the dancers as they danced to the vibrant tunes. In the earlier years the fashion was for an individual singer to entertain, but by the eleventh century groups were singing in polyphonic unison.

A good singing voice was highly prized and it is recorded that during the thirteenth century, old women would teach singing to slave girls, so that they could perform in the royal courts. These groups of female singers and sometimes musicians, contributed greatly to the growth and development of literature and music in al-Andalus.

A good singing voice was highly prized and it is recorded that during the thirteenth century, old women would teach singing to slave girls, so that they could perform in the royal courts. These groups of female singers and sometimes musicians, contributed greatly to the growth and development of literature and music in al-Andalus.

Recent Comments